In 2004, the original NES release of Metroid joined several titles deemed classic enough to represent that period of gaming through revisits on the GameBoy Advanced, and yet that same year also saw a much more thorough revisit on the handheld with the release of Metroid: Zero Mission. Aside from several tweaks within the game, the release returned to the source of the series to establish cannon at ground zero, setting the tone and direction for all subsequent releases.

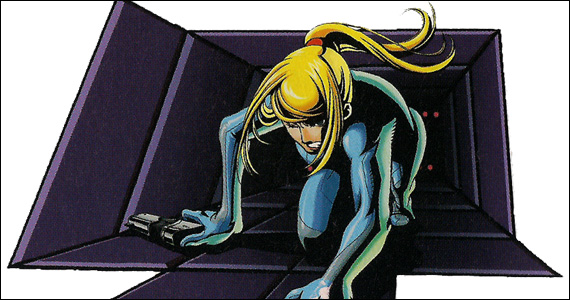

The most significant element of that release was the newly added Zero Mission, a mission that showed Samus Aran stripped of her armor and evading space pirates in the instantly iconic zero suit. It was the emergence of a more vulnerable, but still capable Samus, and a defining moment that opened the floodgates for a greater discussion of the role gender plays within the Metroid series, executed with clever subtlety.

Samus’ gender may have started as a chance decision during the development of the original game, a twist for those that survived that first encounter with Mother Brain, but it was never after as incidental as some would prefer to view it.

There are those who seem to feel that gender is a non-issue, and that to discuss it at all somehow undermines the character and franchise, but the belief that silence is somehow golden here is, of course, completely ridiculous – it isn’t a thought crime to question anything and everything around us, it’s an exercise that appreciates curiosity as much as the truth that the brain is a muscle.

Gender may be considered accidental, given the lack of control any of us possess in the matter before our birth, but that doesn’t preclude that it remains inconsequential afterward. As with the reality beyond a videogame, there are influences and experiences unique to either gender, and Zero Mission cleared a path to examine a Samus who has existed within gaming as an equal with male counterparts, as a character still possessed of femininity beneath her suit of protective armor – a woman equal with men as a woman.

And yet, perhaps the most interesting and unexplored factor in all of this is that the direction of a series overrun with complex issues of femininity, motherhood, and the nature of life – the story of the videogame industry’s most significant female character – has been so largely controlled and developed by a single father figure.

With Other M, the focus on Samus’ femininity turns so sharply in contrast to her previously developed character and actions that it’s necessary to question everything.

Father knows best.

For all the acknowledgment of the Project M collaboration that brought Nintendo together with Team Ninja, there has also been a consistent hammering, a drum beating of the idea that Yoshio Sakamoto is the father figure looming over Samus, having a direct and controlling hand in every one of her missions, with the exception of the 1991 release of Metroid II: Return of Samus on the GameBoy.

Any concerns that this collaboration might yield poor results, or that the introduction of narrative driven cinematic sequences greatly contradicts the running subtlety of the series has been met with the drumbeat that Sakamoto is the primary figure in having brought the series this far, and thus the only man capable of taking the series through another innovation that reinvigorates the well-worn formula.

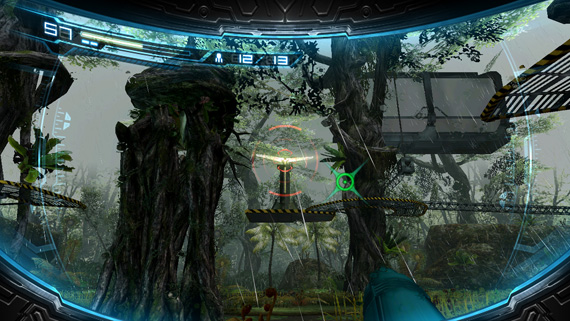

The idea of innovation has ruled the development of a title that doesn’t merely replicate either the side-scrolling releases or the first-person trilogy that was Prime, but explores a new space between those two approaches to the franchise. As a result, Other M offers players a space where Team Ninja’s fast-paced action is simplistically controlled by holding the WiiMote sideways while moving through a sideways view of the environment – with the first-person “behind the visor” familiarity of the Prime series available at anytime by simply pointing the WiiMote straight, ideally delivering a game that appears to offer the best of both approaches.

But just how innovative is it?

That isn’t an easy question to answer. Lacking any real means to gauge innovation, all one can really do is ask several smaller questions in the playing of it all.

Is it innovative to introduce a first-person visor mode where player’s can only move their field of vision? Where their feet remain locked in place following on the heels of a successful trilogy of fully controlled first-person titles? Is it innovative to introduce linear, non-interactive cinema sequences that derail the potential for a more natural in-game narrative to develop, one so pervasively present in every previous release? Is it possible that Nintendo has demonstrated both the limitations of their first-party development ability, as well as the limitations of the controls available via the Wii?

These are simply some of the questions I asked myself while exploring the BottleShip, an environment that offered exploration more as a light distraction that occasionally left me seeking the hidden hatch that would provide another missile tank or charge-accelerator.

The need to discover more necessary upgrades has become a non-issue as Samus manages to retain all of her abilities from the start, limited instead by an agreement that she will only unlock and use them as the need arises – determined by the Commander, Adam Malkovich – of Metroid Fusion fame. As a result, players will often take alternative paths on the first run through the BottleShip, and perhaps begin questioning the chain of command when forced to endure violently hot temperatures until Adam decides to allow use of the Varia suit.

This change in upgrades creates strange situations, such as when players reach a point where the wave beam becomes necessary to activate a switch for instance, but find they must travel back the way they came to reach an ambush point which makes the wave beam an even more necessary allowance, and then causes Adam to issue the command to use it.

I grasp the desire to change the formula, even if it is a founding staple of the franchise. And yet, aside from obvious complaints like those already mentioned, something very precious seems lost in the switch – almost leaving me to imagine what a Zelda game would be like if Link started with the Master Sword but had to wait until Zelda gave him permission to use it.

That might sound like a stretch, but it does get the idea across that discovering these upgrades and being free to experiment with them is at the core not just of Metroid, but of a very specific Nintendo formula that has kept players at titles like Metroid for so many years now.

Elsewhere the camera attempts an admirable job of switching between the two viewing perspectives quickly, though the side-scroll glance can at times make it a challenge to keep track of enemies. Luckily the switch becomes increasingly unnecessary when discovering that the environment offers no real interaction, and thus no real reason to switch into first-person mode – there are no objects to scan for more information or secrets, just obligatory locked doors that require you to switch views long enough to fire a missile and proceed forward.

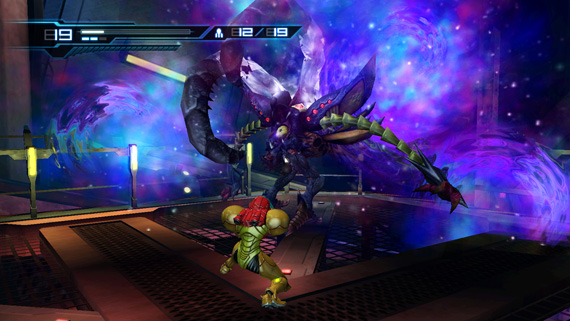

Occasionally enemies try to encourage first-person mode, often offering some moment of slowness that would allow the time needed to switch and fire more powerful missiles, but the game quickly falls into a repetitive system of evading, charging, firing, repeating – except for a very few moments where enemies require a missile to carry them into the afterlife.

On the chance that players get too accustomed to the side-view however, the game forces a few truly bizarre moments of first-person mode, often following a cinematic cue – some leaves rustle, the game forces the player into first-person mode wherein they search out and target some clue to the rustling that then (can you guess it?) activates another cinematic sequence.

It’s a jolting and at times consuming attempt at building an interactive bridge to cover over the passive nature of the experience, especially if like me, you end up searching the screen far too long for some small thing the developers want you to focus on – a patch of slime blending into the dirt comes to mind. Largely I felt left questioning why the first-person mode existed at all for the usage, wondering if its absence made some fear the game might look like a large step-backwards – even if it meant producing a title that at best does a strange dance sideways instead. The core of the gameplay isn’t a write-off, but definitely needs more time in the oven to bake – in fact Team Ninja is the least guilty offender here, offering a more physical and agile Samus that deserves more time to develop.

One bright spot along the way was the ability to turn off or change the environment in holographic rooms – little ideas are always the best type, but are rare occurrences here.

This strange patchwork of game styles that can throw players between viewing perspectives feeds out of an even stranger patchwork of themes tying the Metroid universe together like a thrift store quilt, one that sees several shades of a Resident Evil type experience slip in at times. Enemies like to burst on screen, and the game often forces sequences where players walk in a locked Leon Kennedy type pose to investigate the dark ambiance, while a never ending series of cut-scenes bring us back to the days of storytelling via the original PlayStation.

The plot itself dips a toe into that same territory, bringing about a familiar narrative where cloning allows for the redeployment of original ideas. And much like films with cloning themes, the game’s developers seem to fail at questioning whether they ‘should’ simply because they ‘could.’

Much ado has also been made about Samus’ personal narration throughout the game, a flat performance that has her describe nearly every occurrence as if caught halfway between a therapist’s couch and a Gothic poetry reading.

There’s a very clumsy narrative at work, which invests a great deal of time talking with no particular direction in mind – as if over twenty years of silence has now produced an uncontrollable case of verbal diarrhea. Most often the game attempts to tell the player that relationships exist through Samus’ internal monologue, rather than showing the connections – which then builds into aspiring operatic moments that utterly fail in the absence of any belief in the alleged emotional bonds.

“Show, don’t tell,” is an old rule, but still a good one.

There’s a very strong sense that Sakamoto doesn’t entirely understand the story he so very much wanted to tell. Samus’ narration often functions like that of the original release of Ridley Scott’s BladeRunner, removing all doubt and space to speculate about character relationships, and setting the definitive facts about the Metroid universe – which seems to serve the same purpose as it did within BladeRunner by underestimating the intelligence of the audience.

At times Samus’ narration fails to even make any sense – for instance, she takes to calling a potential traitor the “deleter.” That might make sense if you ignored the fact that she at no point has a conversation with anyone about the concern by either of those names, so that she’s taken to this codeword for use only within her head.

And then there’s the big incident between Samus and Adam that caused her to leave his command, one which verbally becomes a situation between the two of them while visual cues point toward an underlying narrative more about another character linking Adam and Samus before and after. That would be the type of thing easily open to discussion, as if cleverly placed there for just that reason – except that Samus’ narration makes no mention of it. We could assume that it was too painful for her to recount even in her memories, but as if fighting against that possibility she later continues to put a very direct explanation of her relationship with Adam on the official record that removes the opportunity.

What’s left is a painful external telling of everything twenty+ years of releases have already done a much more superb job of telling, potentially making Other M more a strange case of egotism that seeks to permanently set the record straight and function more as a novel than a videogame.

By the time players reach an ending that sandwiches a small slice of interaction between two immense doses of narration – which incidentally prefer to shout about a mother-daughter parallel – what’s left isn’t quite Metroid cart racing, or Samus in Dinosaur Planet, but something far more insulting in the attempt to parade it as a highly polished and definitive product that allegedly encapsulates the franchise while in fact undoing years of careful development. It’s a shocking release that contradicts the franchise and Nintendo’s reputation for polished first-party offerings.

Character development within Metroid has always remained as open as the gameplay – taken or left at the player’s leisure, with as much or as little gotten from the whole of it as each player desired to invest within the searching and questioning. There was something to knowing Samus Aran that shared a bond with the probing available but not always required in discovering the secrets inherent to Zebes and other Metroid flavored destinations.

So much comes down to the characterization of Samus, open to numerous interpretations until the finality this release works to assert. The really unfortunate part is that many seem ready to accept the choices made in characterizing her female identity as an necessary means of making her more than just the typical male hero in a female shell, which was never the case if one paid attention to the subtle undertones of each release. The impression left, if only to me and me alone, is of a developer attempting to make and force a more spoon fed sense of their own product – one perhaps better prepared for by-the-numbers followups.

I don’t have a female perspective to lend the potential debate, but that the most sensible means of stressing a difference in gender has taken the course it has within Other M says something unfortunate about those responsible for writing and developing the character of Samus Aran.

Metroid: Other M

Developer – Project M [Nintendo, Team Ninja, D-Rockets]

Publisher – Nintendo

System – Nintendo Wii

Release Date – August 31, 2010

*A copy of this title was provided by the publisher for review

So, overall, would you recommend a purchase or to avoid it? After reading your review at some points I felt you recommended this game and then at others I got the opposite vibe.

I have the game waiting for it’s turn in my collection so I should be playing it around december.

Comment by EdEN — September 7, 2010 @ 11:59 am

I really can’t recommend it. Replay is a non-issue, and the game manages to trade off more game for cinema as it winds down – where the great ending others told me about is remains a mystery.

It feels like paying for a back-stepping experiment that wanted nothing more from the franchise than the key players, one meant to distill the series and make less of it in order to invite more players to the party.

And that’s a very odd disease going around, because if you have to do that, what was the point?

Why not just make Tecmo’s Space Station BioTerror with a girl in a red suit? I might recommend that for $20. In the meantime I’m going to puzzle over why a series that was treated so carefully for so long ended up here.

Comment by Jamie Love — September 7, 2010 @ 7:37 pm

Well, game is already bought, I got my 70 coins for my Club Nintendo account and I’m waiting till december when it’s Metroid: Other M’s turn to be played. I’ll let you know what I think when I finish it.

Comment by EdEN — September 7, 2010 @ 8:38 pm

cool, I’ll be looking forward to that – also let me know if you do a survey for more coins even though you haven’t played it yet ;)

Comment by Jamie Love — September 7, 2010 @ 8:41 pm

Noooo you’re only to do surveys of games you’ve played hahaha. I’m already platinum for this year so, other than registering games for the extra coins thanks to intend to buy and registering during the first fourweeks from release, all surveys are to br taken until august 2011.

Comment by EdEN — September 8, 2010 @ 12:20 am

All I know is that I hate the new Samus and I can just imagine the meeting that started it all.

“Give her a big rack and tight butt!”

“Even better! Let’s put her in a skin-tight bodysuit!”

“Now let’s give her a blonde ponytail!”

“SO HAWT!!!”

Yeah, that’s what a galactic warrior should look like. In just a couple of years, they turned Samus Aran: Bounty Hunter into Samus: Space Barbie.

Comment by SP — September 10, 2010 @ 1:47 am

A buddy of mine says that the metroid series would never have to deal with any of these character complaints if they went the easy route and made Samus a guy. Strangely I can’t help but feel he is completely correct.

I’ve always felt that fans have projected a lot onto Samus. The concept of her being this super powerful independent woman exists because of huge presumptions. She really is an incredibly underdeveloped character, and that actually worked a lot in her favor because you could then presume everything you want. The real danger exists with actually developing her, because if you make her too capable you’re just giving us another generic and unrealistic character, a woman in man’s clothing where you can literally replace her with a man and nothing changes. However if you make her more feminine and vulnerable you’re stepping on the toes of a fanbase that has already created the character in their head and possibly extending into the territory of making her empty and vapid.

I applaud Nintendo on attempting to do something difficult like developing a realistic female character, but I think they really should’ve stuck to their old approach until they really developed a stronger story with more consistency. I don’t agree with a lot of the complaints that they ruined her character, but I agree that there were a lot of inconsistencies and that the story was stupid as all hell. Which really aggravates me when you consider that the story actually had potential to be something much much better.

Comment by Damo Suzuki — September 20, 2010 @ 7:23 pm

“However if you make her more feminine and vulnerable you’re stepping on the toes of a fanbase that has already created the character in their head and possibly extending into the territory of making her empty and vapid.”

Stop begging the question!

Comment by Joking? — November 3, 2010 @ 6:19 pm