I spend most of my days waiting for games like Deus Ex: Human Revolution to come along; games that do science fiction well, and authentically.

William Gibson has said that all great science fiction isn’t really about the future, it’s about the present—and that’s part of the strength of Deus Ex. At the heart of Human Revolution is the augmentation debate, and within it are shades of modern day quandaries, reflections of the everyday arguments of politics, science, and religion.

Care has been taken here to craft a genuine, believable world. This game doesn’t feel like a caricature; the ideas and conflicts feel true to life, and so does the argument the game hinges on. That fidelity informs Revolution down to its core, and makes it successful.

This is felt most viscerally when the story crescendos; there are several crux moments where the player is involved in arguments with NPC’s and must aim to persuade the individual in question. These conversations feel genuine, rather than scripted, as choosing particular responses can dramatically change the flow and tone of an argument; an option that sounds good could press the wrong button and cause an opponent to completely shut you out, or alternatively, could turn that same person to your cause.

These moments are powerful, partially as a function of their rarity, and feel right in the argumentative climate of Deus Ex, where the fundamental conflict is the augmentation debate raging in the background.

Deus Ex also distinguishes itself with a unique pace—so far as a set pace exists, anyways. The player has an exceptional amount of control over how quickly or slowly the game moves; exploration, patience, and combat roles all serve to influence the speed of the game. Indeed, a player so inclined might spend three hours doing nothing but raiding apartments and reading emails, with not a shot fired.

On paper, the game doesn’t look very long—especially for an RPG. There are only a handful of discrete story missions and side-quests; such that, if I were to list them, you might misunderstand the length of the game. A single mission in Deus Ex could take hours, depending on the mission, the play-style, and the immediacy of the undertaking. The game could run anywhere from twenty-five to forty hours, offering significantly more bang for your buck than other single-player experiences.

More interestingly, it becomes difficult to define what constitutes mission-oriented gameplay and what’s just aimless wandering. Missions and side-quests bleed together with basic exploration; breaking into some random apartment is as likely to yield information relevant to the story or a side-quest as actually following objective markers. I found that information gleamed during one quest might relate to another I was investigating at the same time; there’s a web of themes and plot-lines that run right down to the core of the game, and pieces of them can be found everywhere.

Unlike some comparable RPGs, there’s only one way to start each side-quest, which might make it easier for such quests to go unnoticed—but the trade off is that the development of side-quests is far more natural. Jensen won’t find random citizens with question marks over their heads; the quests all relate to the people, circumstances, and events of the core story. In this way, Deus Ex is a singular narrative, and not a game where the player abandons the core story to participate in trivial tasks for random characters.

The promotion for Human Revolution talked about choice, and that evokes certain images in the minds of modern gamers—dialogue wheels, morality scales—but those things are not really how “choice” manifests in Deus Ex.

Yes, there is a Mass Effect-style dialogue system, and the player is sometimes offered moral choices—but there is no morality scale, no right or wrong, and in many instances these choices influence events little.

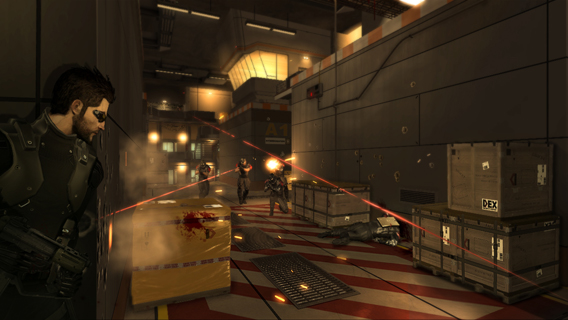

Instead, the real choice lies in the core gameplay, not in conversations or side-quest resolutions. That’s not merely to say the game provides multiple paths; that would be a gross oversimplification. What’s offered is a loose array of options that can be strung together for the player to form his own path. Levels don’t feel ham-fistedly designed to offer paths A, B, or C, but instead offer a natural exploration that can lead to multiple results.

Level design also merges with player progression to provide the player not only with real gameplay choices, but also one of the few examples of true, functioning adaptability in a game.

Instead of leveling up with a series of incremental statistic increases, Jensen gradually unlocks the distinct abilities of his various augmentations. For the player, this means that spending a point, more often than not, unlocks an entirely new aspect to an ability, thereby providing new gameplay avenues.

I found myself saving points, stockpiling them until I encountered situations where they’d best be put to use. For example, in one instance I found an elevator shaft that could be used to more stealthily invade enemy territory—so I upgraded an augmentation that would allow me to fall any distance without taking damage. Later, in order to take position above my enemies, I would upgrade my prosthetic arms to allow me to clear a path of heavy objects—and finally, I would buy an augmentation that would eject explosive projectiles in a circle around me, so that when I dropped down on my enemies from above, I would be able to swiftly dispatch them.

Adam Jensen is a walking Swiss Army knife, and his design provides players the ability to build a character with specific strengths and weaknesses, or, as was my approach, to adapt on the fly to the demands of particular circumstances. It’s an extremely satisfying mechanic, and with the expansive options included in mission designs, it carries the gameplay of Human Revolution on its back.

This is a genre-crossing game with no lines; game elements bleed together and feed into each other, and though it may feel inclined to stealth, the meticulous balance will suit any style of player. I hugely enjoyed the ability to pick and choose when to take a stealthy approach, though I more often employed guile rather than true stealth—using the stealth-based tools to enhance my combat rather than to evade enemies.

Also included are customization and specialization options for weapons. Early in the game the player has a conversation that determines which weapons will be in his inventory when the game begins, but all weapons can be acquired later. The arsenal includes a selection of upgrades—some generic and some specific to particular weapons—that encourage the player to pick a few weapons and stick with them. The upgrades are powerful, such that the revolver—which was initially powerful, but impractically slow—eventually became the most potent weapon in my inventory (with explosive rounds, no less).

Of course, the game is not without its flaws. The otherwise solid inventory makes it too easy to accidentally use a consumable from the quick-inventory wheel, while the occasionally dimwitted AI can hamper the gunplay and stealth mechanics.

Additionally, not all enemies respond well to fire, and enemy types are limited. Human enemies simply come in the small, medium, or large varieties, and even those with augmentations don’t employ them in interesting or gameplay-changing strategies.

More notably though, Human Revolution suffers from Lame Boss Syndrome (LBS); an increasingly common condition in the gaming community. The boss battles aren’t really true to the core gameplay values; while it’s possible to play Deus Ex without killing (or being spotted by) a single enemy, the boss characters must be killed, can only be beaten in direct confrontation, and more often than not, fail to provide interesting opportunities for employing Jensen’s abilities.

Deus Ex also feels a little dated on the technical side. The models of lesser characters are rough around the edges, while facial animations are decidedly behind the curve. Animation in the larger sense is a mixed bag; Jensen’s weapon and combat animations are solid, but many NPC’s rock, sway, and gesture crazily during conversations.

However, when the game enters a persuasion conversation, the quality of animation skyrockets. The subjects in these conversations have incredible natural body-language that can predict their disposition before they speak, wonderfully enhancing the sensation of having an authentic argument with a character.

Human Revolution makes a strong case for art direction over graphical prowess (as if there was any question); though the engine doesn’t do anything special, the gap is closed by exceptional art and design—and I mean truly exceptional. Atmospheric cities, cyberpunk technology, corporate logos and electronic newspapers—it’s all rendered with a rigorous attention to detail that makes the world truly immersive, and an artistic achievement.

Equally notable is Michael McCann’s ominous, exciting soundtrack, which might just have easily felt at home in a film like Blade Runner.

Finally, Deus Ex spoke to me on a personal level that I don’t often find in a videogame. Where many games offer a simplified choice between saving the world with moral integrity, or saving the world through backstabbing and ruthlessness, Deus Ex offers a truer dilemma: you’re not saving the world so much as shaping it, and the imperfect nature of circumstance plays as great a role as morality.

Human Revolution offers four endings, and four dilemmas. Four imperfect directions for the world that are demanded by circumstance, directions that will speak to anyone who has ever seriously contemplated the value of truth in our society.

In the debate of augmentation, the argument that human nature should not be tampered with did little for me; I don’t believe in the spiritual ideal of an immutable human nature—I believe in truth, and the use of truth to improve mankind. The world isn’t so simple, though, and the quandaries of Deus Ex—especially those of the final moments—can’t be solved with just truth, to my difficulty. I think many players will find, as I did, that the result closest to what they believe in will require a moral compromise; where adhering rigidly to personal truths may steer the world in directions not intended.

That sort of nuance, both in the narrative and the gameplay design, is the lifeblood of Human Revolution—it’s what makes this not merely a great game, but also an important one.

Eidos Montreal

Publisher

Square-Enix

System

PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, PC (PlayStation 3 Reviewed)

Modes

Singleplayer

Release Date

August 23, 2011

*A copy of this title was provided by the publisher for review

Thanks for the review Brad! Now I know how I’ll get my next 50 points for my Square Enix Account hehehe.

Comment by EdEN — August 31, 2011 @ 7:24 pm

I have been waiting for this game to come out for so long, so very very long. Then finally it does come out and all I hear and read is good stuff and yet I have been to cheap to buy it. I think I’m broken. If Steam refuses to accept my system of bartering (7 pairs of jeans, 2 guinea pigs and a warm blanket) I may just fork out the 50 bucks.

Comment by Erikmichael Mcd — September 2, 2011 @ 12:32 am

If I had a copy of Deus Ex to spare I would totally make that trade!

Comment by Jamie Love — September 2, 2011 @ 1:06 am