The world did not come to an end last Friday, but odds are that one day, our species will be wiped off the face of the planet, and we will be survived by naught but the machines we made. That reminds me – Gamesugar wishes you and yours a merry Christmas and the happiest of new years!

Anyway, Primordia is an old-school point and click adventure game that imagines such a scenario, wherein robots of various levels of technological sophistication exist in a post-human society where man takes the role of divine creator whose existence is disputed.

What truths will be revealed in this land of rust and light about the time before robot?

The player controls two characters: Horatio Nullbuilt and Crispin Horatiobuilt (robots use the surname suffix “-built” the way that us meatbags use “-son”, making Horatio’s name that much more ominous).

Compared to the other Wadjet Eye point and click adventure games, such as Blackwell Deception and Resonance, Primordia’s is notably more streamlined in terms of sheer playable character count. Horatio is the primary character, and Crispin exists as an extension of Horatio’s body, designed pretty much to reach high or small places, dispense hints, and ceaselessly crack wise (which he does more than the other two things combined).

The puzzles are appropriately mechanical in nature. There is quite the emphasis on the assembly of machines and decoding messages. Primordia places an emphasis less on forcing the player to MacGyver together a solution based on found objects and more on letting the player know what objects he or she needs and then tasking them to scrounge around for the pieces. That being said, there is also a Robot Bible quiz, which is something I’ve yet to see in any other game of this or any other genre.

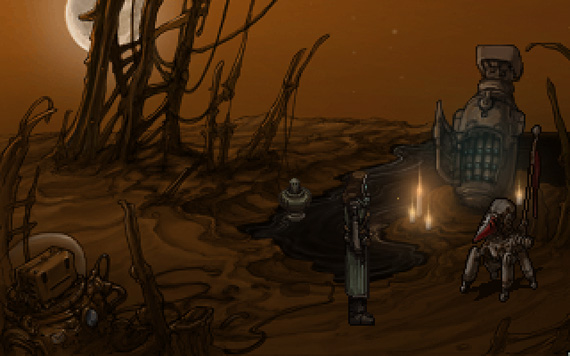

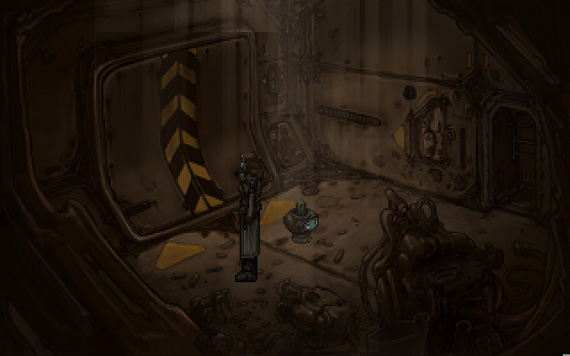

Most of the game’s visuals are remarkably brown and rusty, but given the fact that Primordia is about a robotic society surviving after the end of mankind, the lack of color can be forgiven; I can’t think of a single apocalyptic scenario brimming with color, with the obvious exception of Adventure Time.

These low resolution metallic compositions look amazing, and are accented with the occasional LED or other light source. But the style of forced pixelation oddly stops with the characters who populate the various wastelands and robot cities; as they walk further back into the scene, they shrink, making their pixels a different size than those of the rest of the scenery, which takes away from the “this is an old-timey point and click adventure game” vibe that the game aims for.

Every line of dialogue in Primordia has accompanying voice acting, and the robots therein have voices that run the spectrum from slightly muffled human voices to the stereotypical loud monotone robot voices that would deeply offend any robot that happens to be playing this game (though any machine advanced enough to feel outrage will probably be far too busy tangling with the existential quandary Primordia invokes to do so).

Not unlike The Smurfs or My Little Pony, the fledgling robo-society has its own vernacular tailored to its own species. Dialogue is littered with robotic variations of our phrases and idioms, with copious references to gears and computing. These changes in dialogue range from delightfully clever and world-establishing to just plain groan-worthy; I’m still on the fence about which of the two categories using “b’sod” as a curse word falls into.

Once Horatio and Crispin reach the city of Metropol, the game presents a strangely familiar dispute about whether or not man actually created the first robots. Primordia’s spin on the origin of species is thought-provoking; my mind was wrought with speculation over which side would wind up being right in this game. Clearly, I don’t want to spoil anything in this review, but as I journeyed through Primordia, I found myself the victim of a variant of the Princess Bride cup swap conundrum. That is to say, I’m pretty sure that humans exist, but at the same time, I was worried that the game would feed upon mankind’s vanity and assurance that it indeed exists, and throw some sort of curveball to make this a tale wherein we did not create machines such as the one on which I played this game and am typing this review.

What if they accounted for this assumption that I developed internally rather early into the game, though? I decided to just throw away any assumptions I had, and play this game as if I was not sure if I existed or not. It’s a bizarre mindset to have while playing a game.

Achievements are available for Primordia, which is par for the Wadjet Eye course. These achievements encourage exploration and discourage brute forcing ones way through dialogue branches. These achievements are also delightfully unobtrusive; the list can only be seen through a menu in the options screen, which is a nice change from Xbox’s Pavlovian approach to achievements. Replay value is also aided by a multitude of endings, though the opportunities offered to reach some endings are fleeting to say the least.

The robots in Primordia are just like us; they argue about religion, they have an energy crises, and they have floating sidekicks who constantly complain about their lack of arms – well, two of those three, at least. While the gameplay is nothing new, the story really is an interesting take on the entire “humans are doomed and robots can build other robots” premise, and one that should be experienced by fans of adventure games or robots.