My first encounter with The Red Star was a moment of complete chance. I happened to pick up the September 2004 issue of Play Magazine one morning – bewitched as usual by the shiny cover. Discovering a preview for The Red Star, I was instantly seduced by the visual style and eagerly read about the Acclaim title, which ambitiously aimed to merge elements of both the SHMUP and Beat ‘Em Up games of my youth into a single and instantly addictive action experience.

There was also a clear intention to create a game that was simply fun to play. Between the images shown, and the glowing preview Play gave the title, the only question that remained was whether I would buy the game for my Xbox or PS2.

But this all came crashing down when, with the game essentially completed and reviewed by several journalists, Acclaim went bankrupt in late 2004. Rumors continually surfaced, claiming that company X or Y might potentially bring the title to retail, but in the end gamers would have to wait until April 2007 for XS Games to finally release it.

And if this delay was painful for me, it was undoubtedly agonizing for Ara Shirinian, who worked as a designer on the game,

“…we were wrapping up the game (that’s a whole other story right there). I and the other designers on the project felt like if we had a few more months we could really polish and fix up the most problematic parts, but you never get to truly finish a professional game project, they just make you stop working at some point.”

Recently, I’d stumbled across a site that contained a scan of that same September 2004 issue of Play Magazine, as well as a listing of several boss encounters throughout the game. I was impressed with the layout, and dumbstruck to find that the page belonged to Ara, who created many of the scenarios within the game that have kept me replaying the title to this very day.

My fingers hesitated more than a few times while typing out an email, which soon after began an exchange that has given me a great deal more to consider not only about The Red Star, but about the process and state of game design as it stands today.

If you’ve never played The Red Star, and shame on you, the game doesn’t simply tape two genres of gaming together, but works to create a seamlessly hybrid experience that finds convergence points between the two, creating something unique while familiar.

I’m not aware of a single review that fails to mention the obvious inspirations and nods to games like Ikaruga and Streets of Rage. Even Ara lists influences from titles like Gradius and U.N. Squadron as playing a role in his designs.

While it’s great to discuss sources of inspiration, when sitting down to actually create these sequences, there isn’t a magic “Treasure” button a designer can press to make it all come together so easily however. So learning more about the process involved in drafting and creating these moments that play on in my memory was the most pressing and awkward question I had for him at first.

“My approach to designing the boss battles (there were at least two per stage, and sometimes more, which was a deliberate structural imitation of many Treasure games) was wholly abstract: The gameplay was designed and built around interesting interactions and rules first and foremost, while visuals and context were created only after the gameplay was largely done, and only if they complimented the gameplay itself.

My instructions from my lead, Stephen Dupree, were basically just to make something cool. So I started designing and building totally abstract mini bosses and gameplay scenarios without any regard for what they would represent in literal terms. Without such restraints, I feel that I was able to come up with all kinds of cool interactions that I would not have stumbled upon otherwise.

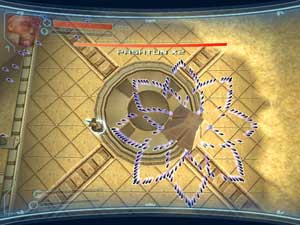

This process worked out particularly well for me because I was good at thinking in pure abstract gameplay terms. I wanted to experiment with spiral and circular shapes for example, so I made several scenarios exploiting that – some worked, some didn’t. We threw away the ones that sucked, and kept the best ones. We ordered them in terms of difficulty, and the art came in later, after their location in the game was established.

One of the greatest criticisms of this process is that you end up with elements that don’t fit the context of the game well in artistic or narrative terms. My response to anyone who says this: either you don’t have enough imagination to come up with a look that fits, or far too much importance is being placed on believable appearances. As long as the execution is high quality, and you don’t get too crazy, players will generally accept at face value whatever you throw at them.

I think a lot of times as developers, we are afraid of inadequacies in our own work in dimensions that players ultimately do not care about or notice, for better or worse.

In a couple of levels we have this weird pyramid looking mini boss, which is probably the most inappropriate-looking mini boss in the game, and of course has never appeared in any The Red Star comic (same for most of the mini bosses).

When you play against it, is the experience ruined or substandard because it doesn’t fit into The Red Star canon, or because you can’t physically justify what is causing it to hover and spin and warp around? It might be if you’re a devotee of the comic, and if you evaluate it as a non-interactive medium, but not if you are actually playing the game. We’re making a video game, not a comic, so the interaction comes first.”

Naturally this seems the logical way to approach videogame design, but it is it typical?

In early July, Insert Credit posted a short piece about IGDA Japan head Kiyoshi Shin’s E3 coverage, in which he focused a great deal on the tendency of game design to place “visual proficiency over functional development.”

It’s no secret that the budgets for games are expanding rapidly to produce graphically superior products, but also that releases are increasingly stagnated and standardized where functional gameplay is concerned.

When asked about current approaches to design, Ara not only has a great deal to say, but offers a degree of insight into the process I was unprepared for, particularly in regards to the approach taken with designing The Red Star,

“There are very few commercial western games that seem to be designed in this way, which is disappointing to me, as is the fact that many designers seem to give narrative context and visual appearances priority over gameplay, whether it’s deliberately planned that way from the beginning or not.

You’ll have to excuse this brief rant, but in my experience as a game designer, I’ve seen many other developers place (what I believe is) far too much priority to narrative and visual structure and so-called “believability” in action games, as opposed to the actual cognitive experience of playing the game itself.

It seems few are able to admit it, but when you are designing a gameplay scenario, ultimately some aspects have to be the foundation of the design, and other aspects have to be shoehorned in afterward. Practically speaking, you can’t give everything equal weight.

Let me give an example.

If you take the top down approach, you generally define the world, characters and narrative first, and your level design, and enemy design in turn follows that. So if the overall story dictates the player encounters a giant spider on level 4, you have to build your gameplay around a giant spider and make it work – regardless of whether or not your game ruleset allows you to do something especially interesting with a giant spider.

This approach is serviceable, but it’s not one that I believe allows you to get the best gameplay possible.

The fact that we were able to enjoy this kind of process (where we developed gameplay as the foundation, independent of what anything looked like or where it fit in the game) was primarily enabled by the fact that we had an incredibly robust toolset which already went through the wringer of a whole game lifecycle (Vexx).

By the time we started The Red Star, the designers were able to design, implement, test and polish complete gameplay scenarios where the visuals were nothing more than a bunch of collision boxes stuck to each other. Only after we got to the point where the gameplay was good, did we work with artists to replace the boxes with real visuals that complemented the design.

All things considered, I think it worked out decently.”

And where The Red Star is concerned, I completely agree that it did.

Naively thinking that I grasped the idea however, I asked Ara the following:

“Increasingly it seems that the games of my youth had narrative that emerged from the design, much like the way Kojima talked about Metal Gear at GDC this year as a result of gameplay solutions to technical limitations. But with this generation of hardware it seems that the entire emphasis is placed on the narrative, and everything is shoehorned into that. In fact it seems like handheld games are becoming a refuge for thoughtful design. Do you think it’s merely a matter of the technology shifting the emphasis? Or was there a point at which the industry shifted toward narrative as a primary concern?”

His immediate response was,

“I don’t think it’s a technology-induced phenomenon at all. There are multiple other reasons.”

And as he began going through these reasons, it was clear that his thoughts on the subject run much deeper. In fact, his response was so much greater than any words I might scrape together to encase it, that I’m just going to shut the hell up and let you read them in their entirety.

It’s not light reading, it’s essential reading, with a thorough comprehension of ideas we tend to only ever hear from designers in snippets and sound bytes.

—

1. Lack of a deep understanding of the medium

Design, actual real game design, is hard. Not hard in an overcoming a challenge with enough effort or money way, but hard in the way that a Russian math professor says something is hard. And few developers really know how to design well. Good design is not taught or communicated well, except in very limited contexts.

Developers are still stabbing in the dark all over the place with the way they practice design, as well as the way they talk about it in conferences. This leads to the proliferation of confusion as much as it does good design sense. This is evidenced by the fact that our games are looking better and better, but they aren’t getting better on average at all.

2. Emphasis on visuals over interaction

This is really a very human side effect of the way games are played and sold, so it’s hard to imagine the quality of games over time developing in any other way. Think about this – everything you hear and see about a game, before you actually play it in fact- is essentially visual. Even when you start playing a game, the visuals color your impression of the game. It takes you about 10 seconds to get an intuitive feel for the visuals of a game. It can take minutes to hours to get an intuitive feel for the mechanics – the actual gameplay- of a game. So its no wonder that visuals are emphasized more over gameplay. You can always see what a game looks like before you play/rent/buy it. You can never see what a game plays like before you actually play it.

This is a vicious cycle – as humans we have more experience in non-interactive visual communication, which has existed for thousands of years, than we do human-computer interaction, which has existed for what, 40 years? Because we suck at interaction design, and are already good at visual design, we concentrate our resources on improving visual design. So visual design gets more attention and development, while interaction design just gets shoved further and further back into the closet.

Technological development is only indirectly related – during the short time where we could not spend money or time on high tech solutions, we were forced to fall back on actual game design. Now, since technology is exploding, good design is not “necessary” for a game to get noticed, garner attention, or even become a blockbuster hit.

3. Most gamers aren’t even gamers and they don’t even know it

By this statement, I intend to say that most people who play games very often enjoy them for reasons very different from the actual mechanics of the game. This is not bad or wrong on the player’s part, its just a consequence of the games market’s concerted effort to constantly expand their user base in order to increase their profit potential.

Because the market is so huge, I think the majority of game players are not specifically seeking a “good game” as much as they basically just seek some kind of generalized entertainment medium that will keep them occupied and entertained. If it has some novelty, if the imagery makes you feel like a badass, if it momentarily distracts you from your boring or stressful life, if the visuals and explosions look cool enough, hey its worth spending some time on, and in today’s world that makes you a gamer if you spend enough of your life on it.

However, the segment of the market who plays games primarily because they appreciate the interaction design is limited. I’m not even sure if the mass market at this point can even recognize or appreciate good design if they see it – which is less a comment about gamer snobbery as it is about just how big and fast the game market has actually grown. In the same way that many people ran out of theaters in panic when they saw the first ever movie shot of a train running toward the camera, the mass market needs to have a certain amount of exposure to games before they can become discerning.

4. Marketing / PR / Lip Service / Hype

There is an insane amount of “expert” media hype about games, genuine as well as manufactured for whatever reason. This coupled with the huge new mass market of gamers means that more people than ever look to this hype machine, in the aggregate (e.g. metacritic), for permission to like certain games.

Conversely, it also does not give gamers permission to like other types of games that don’t fit the popular “cool” genres or themes, even though those types of games may actually be very, very good.

Consequently, we end up with an idiosyncratic standard of what constitutes a good game, which is a mishmash of sales numbers, review scores, and the “coolness” of a particular theme or character or idea, all of which are hopelessly intertwined.

*A tremendous thanks goes to Ara Shirinian for welcoming my questions and for helping to produce this article. You can pay his website a visit at shirinian.net.